Husani Oakley’s Design Journey

For his design journey, Husani Oakley is interviewed by friend and fellow design and tech innovator Robyn Kanner. "I met Robyn Kanner during a meeting with the Obama administration at the White House a couple of years ago, and within about thirty seconds, realized that she was someone I needed to know. She’s brilliant, brave, and most importantly, one of the most honest and open people I’ve ever met. Given the chance to choose a person to talk with about my journey, I wanted someone who was honest about theirs." —Husani Oakley

AIGA - Robyn Kanner

Robyn Kanner (RK): When you were ten years old, how would you have answered the question, “What do you want to do when you grow up?”

Husani Oakley (HO): I wanted to be an astronaut. And everybody said “No, no, no,” but it was serious for me. I went to the same middle school as Buzz Aldrin—in fact, in 2016, they renamed the school after him.

RK: Do you think that because you were surrounded by unapologetically black culture so young, it helped influence the way you owned your identity?

HO: From fifth grade on, we moved to the suburb in north New Jersey where I live now. Suddenly, I went from being entirely surrounded by people who look like me to being surrounded by people who look like everybody – and from private school to public school.

It's like my first week in fifth grade in public school in a crazy diverse class–there are white people, Asian people. I've only seen these people on TV. That's awesome. But it was a weird time for me because suddenly I'm surrounded by all these different types of people and the freedom of a public school vs. a private school. I think I had a reputation already. “Oh, you're the smart one.” So I ended up in groups where even though it's a super diverse town and my class was diverse, I was with a bunch of white kids.

“I'm beginning to have all these weird thoughts about different ways to view commonly used things. I realized, it's okay to be this wacky, geeky person. It's fine. Why not?”

RK: Of course, being in that environment. I grew up in Fairfield, Maine, in a very small town. And I think I internalized a lot of homophobia and transphobia just because it was so deeply ingrained in my culture. Did you internalize your identity?

HO: It wasn't and it became a thing at the end of eighth grade. I was oblivious. I was just like, "you're my friend." I'd hang out at my friend's houses, in their mansions. I'm from Montclair. Their parents would treat me like they would treat everybody else. I still remember a Halloween where I went to go trick or treating in my best friend’s neighborhood. I was Freddy Krueger or something so no one did know who I was.

Some mother comes out and says: “Oh no, it's little Peter and oh, I don't know you. Is that so and so, is that so and so.” They’re obviously white names. But you don't know me because I live on the other end of town. It wasn't until later I realized “Oh, you have a problem with the fact that I'm not like y'all.”

RK: Right, but you still have the unapologetic thing with you, right? Like you kept that and that’s huge.

HO: Yes, it was like, if you don't like me, I don't know how not to be me. I mean beyond the whole awkward kid thing, everyone just watches you as the gay black kid, the gay, black/Puerto Rican kid. My mother's black, my father's Puerto Rican. Puerto Rican and Dominican. I don't know where I am when you have to fill out a form, and you got to pick an ethnicity.

RK: This is not a binary choice. It's blurry. Why is this a radio checkbox? Was your first mentor in design or was it in tech?

HO: The first person I would consider a mentor was my music teacher. When I got out of high school I stopped caring. I thought, boy you know what? I'm going to be me. I don't care. I had discovered music at that point so the career decision was, okay, astronaut, well, while I’d still love to, I hope that by the time I'm an adult, I can just hop on a ship to Mars. So I don't need to be an explorer. I can be an artist and you need artists too, right?

My high school music teacher/private instructor was like my father figure, my mentor. Personally, exactly whom I wanted to be when I grew up. I remember I had a Music Theory class and the second day he went off on this tangent about how he visualized time, not as linear but as circular. When you picture a calendar, you think of this sort of linear flow. He thought of a calendar as a circle. And he drew this diagram on the chalkboard.

So I'm beginning to have all these weird thoughts about different ways to view commonly used things. I realized, it's okay to be this wacky, geeky person. It's fine. Why not?

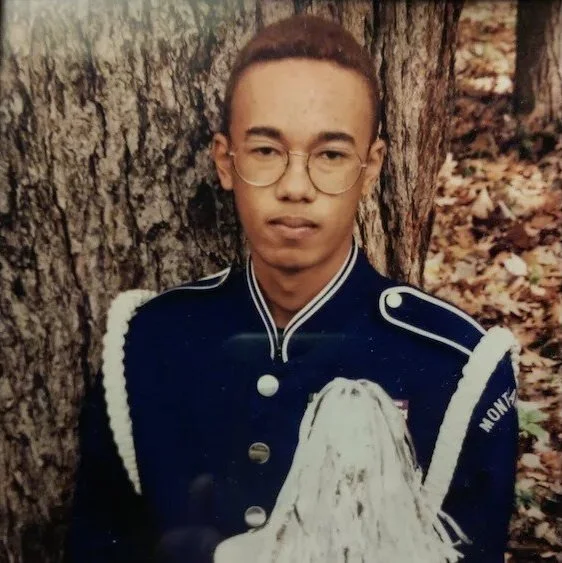

Oakley as a member of Montclair High School's marching band, 1995-1996. Image courtesy Husani Oakley.

RK: Did that thought process influence what you decided to do at the end of high school, when making decisions about college?

HO: It's funny because when I think about it, there's a pattern, but you don't see the pattern when you're in it. So I actually sued my high school. The school had just started a Junior ROTC Program [Reserve Officer Training Corps] and a friend of mine had an issue with it politically. He made a satirical recruitment poster for the program. And on the front page, it said “Are you a black student? Do you have a C- average? So, join JROTC and be the first to be shipped off in the next war.” I supported him, I wasn't necessarily political but I knew right from wrong. I knew it, of course it's going to be the C- average black kid that go to ROTC.

Another acquaintance saw the poster and told his father, who was a teacher, and then the father told his colleagues, and it suddenly became a whole big thing. My acquaintance was forced to apologize to the school over the morning announcements for the racist pamphlet he had made. The intent was being ignored.

I put together a group of acquaintances. We put together a series of flyers that we designed on my home computer. I printed them at work. I was, by the way, running a computer consulting company. My favorite one: “Why do male sports receive more funding than female sports? Why do white sports receive more funding than black sports?” So we snuck into school after school is closed one day and we put the flyers on the wall. The next day, everyone had seen them. Then my accomplices totally ratted me out. I got called into the principal's office. And, she said, "So we know these flyers were you. So we're suspending you for seven days."

RK: Well, they were trying to keep you in your place. Like shut up and just go to class.

HO: Yes, set the tone; "don’t cause noise as you grow up." So I'm suddenly back to the good art kid. I'm back to fifth grade goody-two-shoes. I go to a pay phone and call my mom. "What!? Husani suspended? No, this will not stand." We filed the lawsuit in Montclair's crazy progressive town.

RK: Was that your introduction to what design could do for social change?

HO: I realized that it was possible to take a thought, make it tangible and put it in front of somebody and have them react to it. I realized this stuff doesn't necessarily need to stay in my head. I can make things and I understood it as communication through art, as visual art.

RK: So when you were able to change the conversation, with internet bubbling up, how did it influence your approach?

HO: High school's done. I convince my parents that I'm not going to go to college right away. I'm going to take a year off and my mother is like "Are you out of your mind!?"

I got involved with the New Jersey community theatre scene. I did this internship randomly. I'm up at two in the morning one night, and I see a job posting on the internet. This job is in New York City. And being from the New Jersey suburbs New York City is just far away and you're from rural Maine. We can see the skyline from the town that I grew up in, but you just don't go there.

I got this internship at agency.com. I was a dev [abbreviation for developer], because that's what I said I could do, right. I was about to turn 18, I don't know anything about anything, but I knew that I wanted to communicate. My first job day on the job, they say: “So you are on the British Airways Team. Go, learn it. Communicate. We're going to give you stuff and you're going to make it, you're going to build it.” This is 1997.

RK: What obstacles did you deal with during that time?

HO: I was the youngest person on this team with no college experience, six months out of high school, now with a job in downtown Manhattan.

RK: Were you out?

HO: Yeah, not that I knew what that meant. But I had gay pride rings hanging from the wall of my cubicle. One day, a colleague asks what they were, and I couldn’t quite talk about it.

RK: We didn't have the language at that point, right?

HO: Right, I had no clue, so I’d just change the topic. I was just completely naïve, I am a kid and I'm doing adult-ass work. I have no idea what I'm doing and I have not experienced enough of the world to understand how any of this works. I'm working in London. It's my first time out of the country. And I'm leading this team: “I convinced you to give this to me, and I should have not have convinced you to give it to me. I should've been honest with you and told you that I don't know what I'm doing.”

Photo courtesy Husani Oakley

RK: But honesty doesn't get you in the room. Something that I think about a lot is legacy. When you think about the legacy you're going to leave in the world, where do you think your impact lies?

HO: I think about the Voyager probes and I think about how much I would have loved to be in the room when it was sent out. There's a sketch of humans, with these songs and pictures. Thinking about how we, as a species, are presenting ourselves to a complete unknown, a massive question mark comes to mind. It makes me think how frustrating it is that we, as a species, take these stupid, superficial differences and make them into a real thing. That’s impact on real lives. It makes me violently angry. We're one species, head in clouds and all, but we are so behind in having a framework upon which we can have meaningful conversations about differences.

I have huge hopes that what makes us really interesting as a species is that we use tools and communication. So design is no different than the use of the hammer, no different than the invention of fire.

RK: It's interesting because you're still the person you were in high school, trying to solve the same root problem. When you think about the progress that shifted from your high school to now, do you feel good or do you wish it was more significant?

HO: Both. Having the internet, I could and did interact with people who were not in my immediate social groups. What frustrates me are the job divisions: tech; UX; design. We come with different experiences, expertise, and practices. And how amazing is it, we can all put our specific expertise together and make something and put it in front of another human being and have them interact with it.

Photo courtesy Husani Oakley

RK: I know we all face obstacles when we decide to become a designer. Can you tell me about a few that you overcame?

HO: Frankly, my biggest issue has been convincing some folks to even consider me a designer in the first place. It goes to a larger issue, one that’s still constantly debated—what is design? A lot of my agency career was spent convincing creatives that technology is a creative medium. I created with code, like a copywriter creates with words. Or like a digital designer creates with pixels.

My teams would be in what I call the “nerd basement”—we’d be given a design to execute, our opinions ignored, our desire to be a part of the storytelling process laughed at. It took me quite a while to figure out a way around that.

I tended to be the person who sat between the creative and technical teams, partially because I was more extroverted than other technologists, but mainly because I only use technology in service of a story. What's the point, otherwise? I'm not a scientist. I'm an artist who uses science. But doesn't every artist? Doesn't a painter care about their brushes, their canvas, the chemical composition of their paint? Why is technology seen as different?

“I only use technology in service of a story. What's the point, otherwise? I'm not a scientist. I'm an artist who uses science.”

RK: How’d you use that in your work?

HO: Eventually I realized that my appeals to emotion or fairness would always be ignored, because life isn't fair. So I began to prove my point. As I left hands-on code for management roles, I'd be sure to identify other technologists who thought like me and get them in the same room as designers and creatives. We had to show that we spoke the language of design, not just 1s and 0s. Had to get over some nerd basement stereotypes. Part of what helped me overcome that issue was the democratization of technology. The time to create something meaningful is certainly smaller than it was, say, 10 years ago–I think it's easier for me to show that my work is about a story, not "just" engineering.

RK: Do you have a favorite designer?

HO: I want to be Nicholas Felton when I grow up.

RK: Did you have a mentor?

HO: I've never had an official "mentor," per se, but I've had bosses that have acted as mentors. One boss who immediately comes to mind was my supervisor at a point in my career where I thought I knew everything. I'd been managing ad agency teams for years, and had just started a new director role in a new city. This boss taught me that when dealing with clients, soft skills tended to be more important than hard skills.

He told me to stop thinking of presenting work as presenting work, but instead try to get into the mind of the client. What do they want? Not from a work perspective, but from a human perspective. Are they trying to impress their boss? Get a bonus? Or are they focused on their daughter's recital next week? Show some empathy for your client, some human-level understanding, and figure out the best way the work you're presenting can help them get what they want. That was the best piece of advice anyone's ever told me.

“As designers, our job is communication. If we can't do that, because we don't understand our audience–because we are culturally removed from them–how can we possibly be successful at our jobs?”

RK: Do you think design has changed since you became a designer? I think in some ways it has but it some ways it's the same—just solving problems.

HO: This is something that has always fascinated me, since I got my start in the early days of the dotcom boom. As media come and go, we adapt our techniques and toolsets for those more appropriate for the medium-of-the-day, but what we do hasn't changed much. We solve problems, we communicate, we convince people to think a certain thought or feel a certain feeling. We're a visual species, designers communicate with visuals. But take Alexa or Siri. There's design there. Just because the interface isn't visual doesn't mean creation of a communication paradigm isn't design. The tools change, but what we do hasn't.

A typical ad agency creative team is an art director and copywriter. Even though lots of copywriters design, and lots of art directors write. Does the agency team of the future include a technologist? Maybe. Does it mean that art directors write code, and copywriters crack open Photoshop? Sure. It's all "design," it's all problem solving, it's all communication.

RK: Do you think design is lacking diversity?

HO: Of course. As does tech, as does sales, as does science, as does politics, as does Wall Street, as does every core industry in our society. Americans lack a sense of history–which, I think, is part of our strength and a major part of our weakness. In my parents' lifetime, I wouldn't have been able to use the same water fountain as everyone else in certain parts of this country. In my parents' lifetime! Everyone acts as though the day the Civil War ended, racism was done. Like turning off a light switch. And then it was quiet until the ‘60s, when a nice minister did some marches, and then poof–racism gone again. And, of course, we've had a black president, so everyone's equal, and if you haven't "made it" in America, it's your own damn fault. It's frustratingly ahistorical.

RK: How can people solve that? Whose job is it to solve that?

HO: Most hires come from a person's network. Companies lack diversity because most people don't have diverse networks. People aren't being penalized—yet—for their lack of diversity. They'll eventually be penalized by the market, though. As designers, our job is communication. We create things that make an audience think what we want them to think, do what we want them to do, buy what we want them to buy. If we can't do that, because we don't understand our audience–because we are culturally removed from them–how can we possibly be successful at our jobs? How does a monolith communicate in age of rapid societal change? Sponsoring diversity initiatives isn't enough. Hiring a few interns from HBCUs isn't enough. There's a focus at the very bottom, as if pipeline is an actual issue, and a few names at the top. That ain't enough.

“Show some empathy for your client, some human-level understanding, and figure out the best way the work you're presenting can help them get what they want. That was the best piece of advice anyone's ever told me.”